Cloud Brocade by Philip Beesley Arhitect Inc.—http://philipbeesleyarchitect.com/sculptures/1114-1214_Cloud-Brocade/index.php

This is an excerpt from the ‘Self-Positioning Essay’ written in May-June 2014 for Central Saint Martins, MA Innovation Management course.

According to Nicholls & Murdock (2012 p. 35) there are various definitions for social innovation in the literature review, including Stanford University (Phills Jr., Deiglmeier & Miller, 2008), OECD and NESTA (Bacon et al., January 2008) most of them describing it as a field related to ideas, products, services, for the public good.

Furthermore, paraphrasing the same authors, social innovation is defined as ‘innovations that are social both in their ends and in their means’, a complex process of introducing new ideas—products, models or services— that will break the mould of existing social relations and collaborations and that will enhance society’s capacity to act (Nicholls & Murdock, 2012 p. 35). Social innovation emerges from ‘contradictions, tensions and dissatisfaction’ that are caused by new knowledge, new needs and new demands marking the transition from an individual to a collective perspective and by the philosophical view that societies are plastic and human beings are constrained to ‘resist the present’ (Nicholls & Murdock, 2012 p. 34).

Also social innovation should not be treated as a sub category of technological or economic innovation, big-scale ‘political programmes for structural or systemic change, or programmes to extend rights’, but more as a top level category closely intertwined with the others. (Nicholls & Murdock, 2012 p. 36)

Some of the main factors that led to an increased focus towards social innovation were the ‘wicked problems’ (Reyner, July 2006)—world crisis such as the failure of traditional market capitalism (Murray, 2009), the failure of contemporary state welfare systems (Mulgan, 2006), global resources depletion, social fragmentation, increased cultural diversity, growing inequality, changes in behavioural patterns associated with the ‘challenge of affluence’ or a decrease in individual well-being and happiness (Nicholls & Murdock, 2012 p. 8).

In their paper called ‘The Open Book of Social Innovation’ Murray et all (March 2010 p. 3) highlight:

‘Social innovation doesn’t have fixed boundaries: it happens in all sectors, public, non-profit and private. Indeed, much of the most creative action is happening at the boundaries between sectors.’

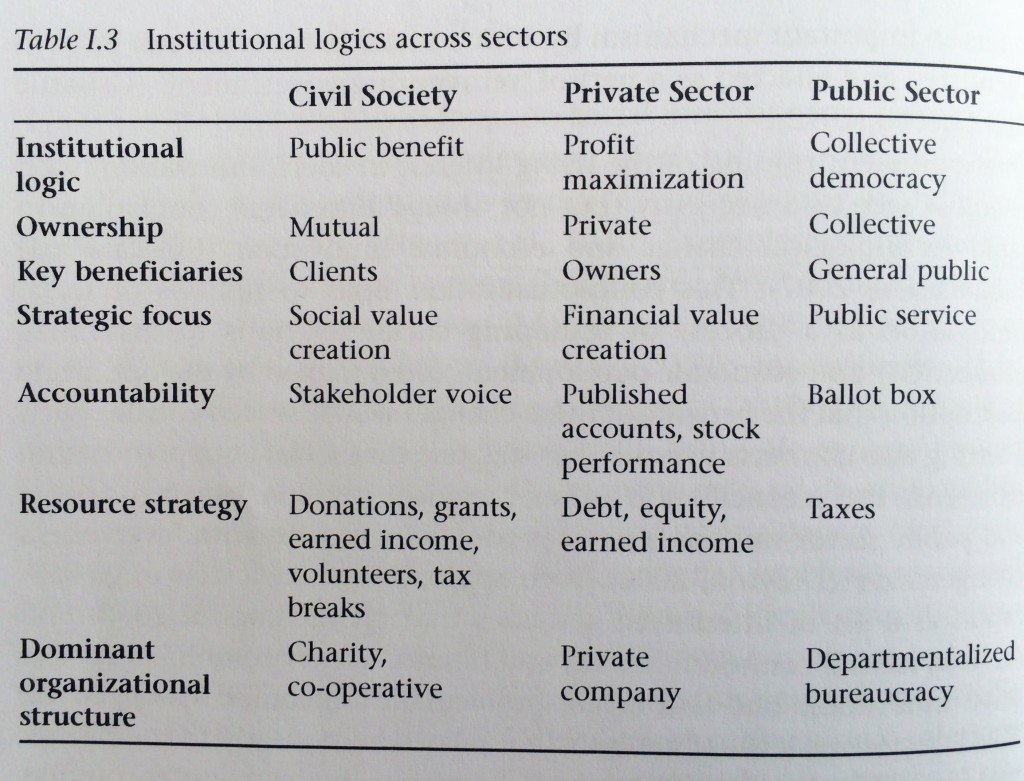

As seen in Fig.1, these three sectors of society—civil society, private and public—include certain ownership structures, various key recipients, unique accountability system of governments, custom resource acquisition and primary organizational forms. (Nicholls & Murdock, 2012 p. 9)

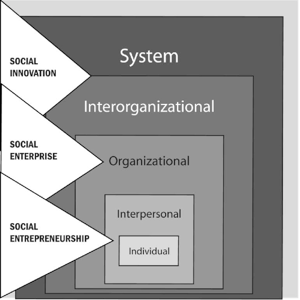

In an analysis of these sectors, Nicholls & Murdock (2012 p. 9) conclude that they can be ‘conceptualized as a Triad represented in stability as a triangle’ (Fig. 2) and that at the intersection of these three points are sited a variety of heterogeneous institutional and organizational forms that facilitate social innovation activities.

Firstly, between the civil society and private sector are found the social enterprises. According to Westley & Antandze (2010) a social enterprise,

‘though it may respond to social needs, is a privately owned, profit-oriented venture which markets its own products and services, blending business interests with social ends.’

Secondly, between the private sector and public sector are hybrid public-private partnerships that create ‘new models of welfare provision outside, but in tandem with the state’ (Nicholls & Murdock, 2012 p.10). It is in this sector where we find the concept of social entrepreneurship. Whereas the concept of social enterprise is mainly oriented towards the organizational form and mission, according to Phillips et all (2008) cited by Westley & Antandze (2010) social entrepreneurship is a human-centred notion that emphasizes the personal qualities of a person who starts a new organization.

Thirdly, between the state and the civil society exist forms of ‘shadow state’ (Nicholls & Murdock, 2012 pp. 10-11) where community organizations, charities and non-governmental organizations coexist and act as surrogate state. It is at this point where one can identify social innovation. If social enterprise addresses the organizations and social entrepreneur focuses on an individual and both of them are profit driven, ‘social innovation does not necessarily involve a commercial interest, though it does not preclude such interest’ (Westley & Antandze, 2010). Social innovation is more definitively oriented towards making a change at the systemic level (Fig. 3).

Phills et al. (2008) cited by Westley & Antandze (2010) states that:

‘Unlike the terms social entrepreneurship and social enterprise, social innovation transcends sectors, levels of analysis, and methods to discover the processes – the strategies, tactics, and theories of change—that produce lasting impact.’

In conclusion, the notions of (1) social enterprise, (2) social entrepreneurship and (3) social innovation are closely related to each other. As Westall (November 2007) stated ‘each of these terms reflects different cuts, or perspectives, on reality.’ That means a social entrepreneur can be a part of a social enterprise and, at the same time, can contribute to the promotion of social innovations.

Figures Table

Fig.1 Institutional logics across sector Nicholls, A. & Murdock, A. (2012), p.10, Social Innovation – Blurring Boundaries to Reconfigure Markets. United Kingdom, Palgrave MacMillan.

Fig.2 Social Innovation as a boundary blurring across institutional logics

Nicholls, A. & Murdock, A. (2012), p.11, Social Innovation – Blurring Boundaries to Reconfigure Markets. United Kingdom, Palgrave MacMillan.

Fig.3 A systemic view of innovation.

Source: Westall, A. 2007. How can innovation in social enterprise be understood, encouraged and enabled? A social enterprise think piece for the Office of the Third Sector. Cabinet Office, Office of The Third Sector, UK, November. Available at http://www.eura.org/pdf/westall_news.pdf (accessed 10 October 2008)

Bibliography

Bacon, N., Faizullah, N., Mulgan, G. & Woodcraft, S. (January 2008) Transformers: How local areas innovate to address changing social needs. NESTA [Online]. Available: <http://youngfoundation.org/wp-content/uploads/2013/02/Transformers-How-local-areas-innovate-to-address-changing-social-needs-January-2008.pdf>.

Mulgan, G. (2006) The Process of Social Innovation. MIT [Online]. Available: <http://www.socialinnovationexchange.org/sites/default/files/event/attachments/INNOV0102_p145162_mulgan.pdf> [Accessed May 2014].

Murray, R., Caulier-Grice, J. & Mulgan, G. (March 2010) The Open Book of Social Innovation. In: NESTA (ed.). NESTA: NESTA.

Nicholls, A. & Murdock, A. (2012) Social Innovation – Blurring Boundaries to Reconfigure Markets. United Kingdom, Palgrave MacMillan.

Phills Jr., J. A., Deiglmeier, K. & Miller, D. T. (2008) Rediscovering Social Innovation. Stanford Social Innovation Review [Online]. Available: <http://www.ssireview.org/articles/entry/rediscovering_social_innovation/> [Accessed May 2014].

Reyner, S. (July 2006) Wicked Problems: Clumsy Solutions – diagnoses and prescriptions for environmental ills. Available: <http://www.insis.ox.ac.uk/fileadmin/InSIS/Publications/Rayner_-_jackbealelecture.pdf> [Accessed May 2014].

Westley, F. & Antandze, N. (2010) Making a Difference: Strategies for Scaling Social Innovation for Greater Impact The Innovation Journal: The Public Sector Innovation Journal, 15(2), 2010.

Pingback: viagra pill 50mg

Pingback: ica apotek

Pingback: apteka zamówienia przez internet

Pingback: wind creek online casino real money